Structural transformation in South Africa

is it really happening?

Yes, it is. South Africa doesn’t grow much, but it moves.. More to the point, I saw a (policy) paper other day where the authors argue that the South African mining sector has been in decline for some time and, because of that, it needs policy support. This sort of commentary gives the opportunity to apply economics so that, hopefully, we get a better understanding of where South Africa is in terms of comparative development and what the policy priorities really are. For that, let’s start by looking at some data and theory.

The new Kaldor facts of growth, advanced by Jones and Romer, highlight the roles of ideas, institutions, population and human capital in the process of development. And unified growth theory, advanced by Galor, highlights how economies change over time.

Unified growth theory divides economies into three regimes. The Malthusian regime in which increases in income are temporary, say, shocks have no long-run effects on income. Then there is the Post-Malthusian regime in which some technological progress and industrialization take place, income increases and human capital formation starts taking place as well. During this transitional period, urbanization also takes place. Lastly, in the sustained growth regime technological progress and industrialization take off and demand for educated workers who can operate technologies increases. In fact, because of technological progress, human capital returns increase and it takes a central role in the production process. In addition, fertility rates see a reduction and the demographic transition takes place.

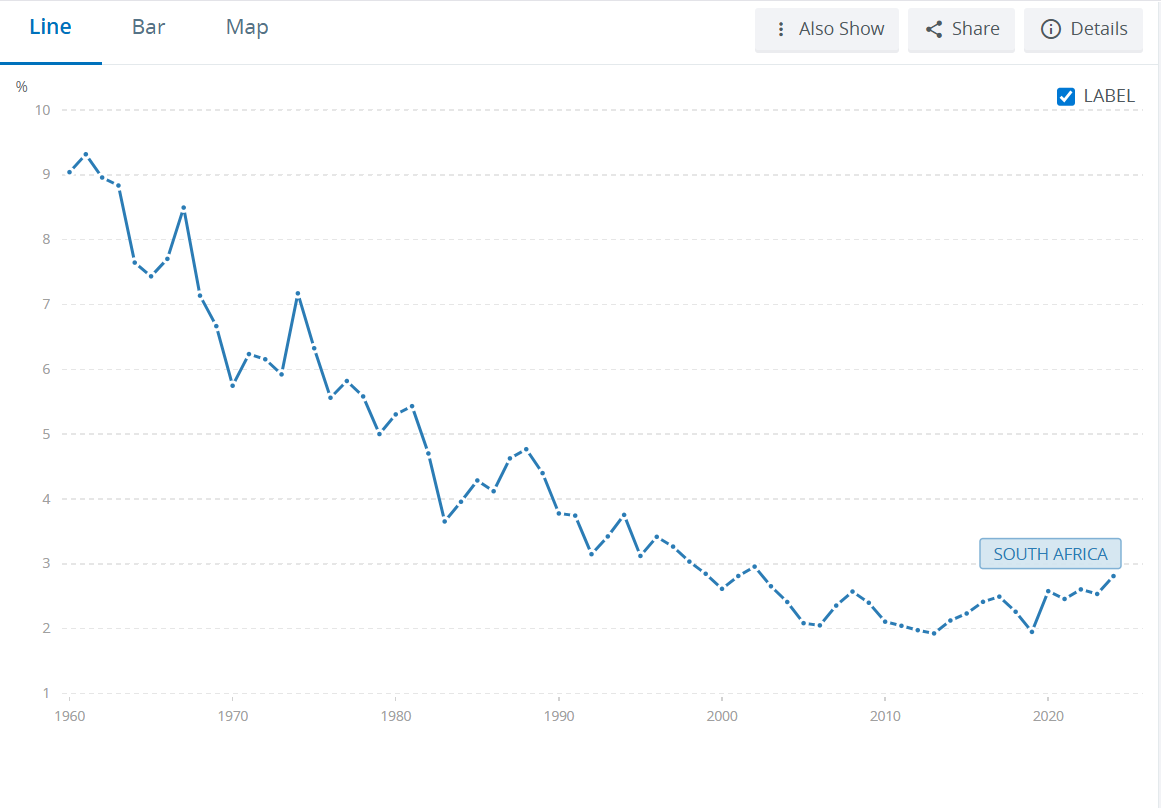

Let’s borrow from the above and see where South Africa is. The picture below depicts agriculture, forestry and fishing, value added (% of GDP). It illustrates the steady decline of that sector in South Africa. This is expected. As economies grow, develop and prosper, people migrate to cities, urbanization thickens and less and less people live out of the primary sector. In addition, the primary sector doesn’t demand people with skills to work there. The sector isn’t about brains, it’s about brawn. The primary sector doesn’t incentivize human capital formation. The primary sector is very unequal. It isn’t about good jobs.

Let’s see now how manufacturing has been doing in SA. A number of people in SA also advocate for policy interventions in order to ‘save’ South African manufacturing. The picture illustrates a decline over time. Differently from the primary sector, the decline in manufacturing starts in the 1990s. Is it expected? Yes, it is. Similar developments have been happening in the UK, US and even China. For the South African context, automation and globalization are changes to keep in mind.

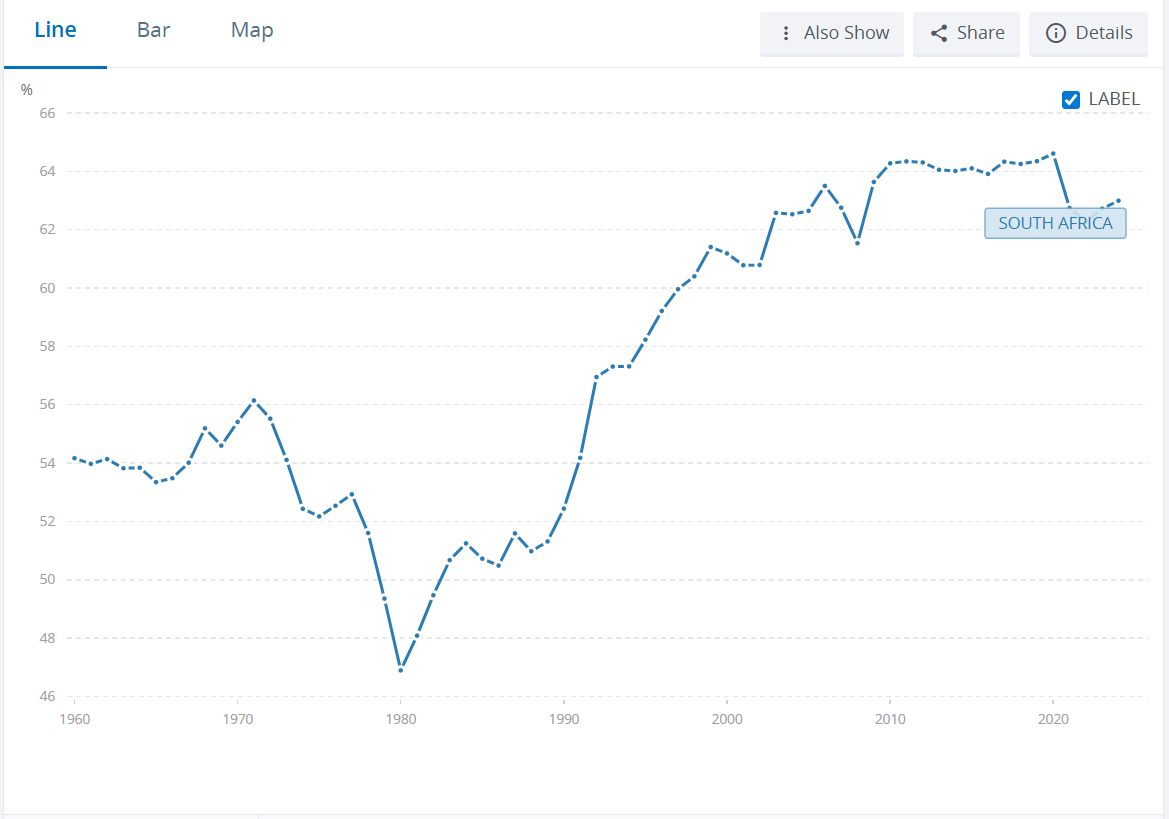

What is then really playing an important role in the South African economy? Let’s take a look at services. The picture below illustrates the consistent increase in the share of services to GDP. Does it make sense? Complete sense. The services sector is a modern, soft, urban sector of any modern economy. In addition, it demands people with skills, brains, in order to work there. So, it incentivizes human capital formation. It’s about good jobs.

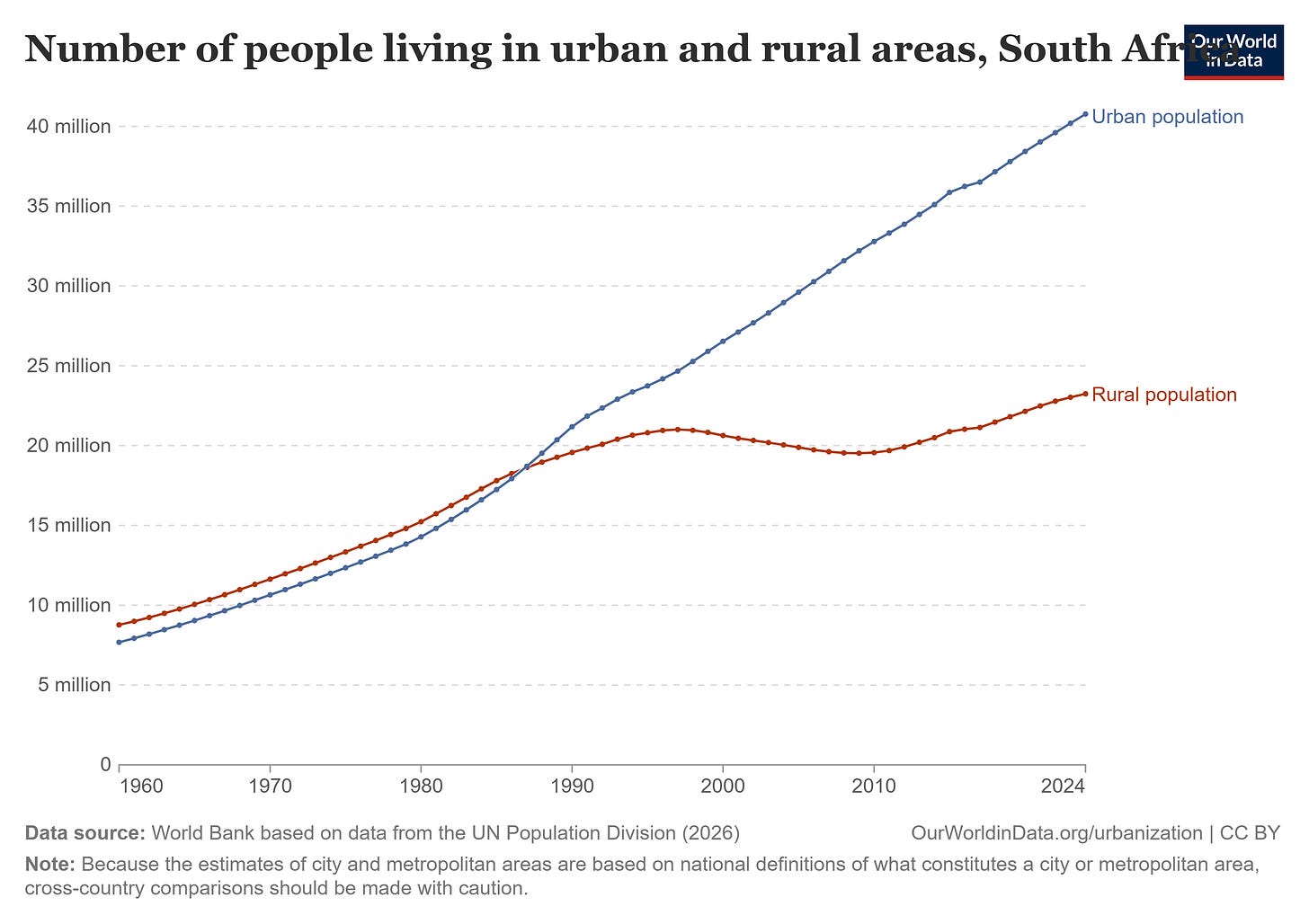

Let’s take a look at urbanization in SA. Urbanization has been on the rise for quite some time. And the number of people living in rural areas has been stable since the 1990s. South Africa is becoming an urban society, and that has serious implications for urban planning. Cities are places where people can acquire health and education more easily, schools and health centers are not too far, and (good jobs in the services sector are available). But recall, the services sector demands people with skills. So we need skills, brains. In addition, ideas and technologies spread faster in cities.

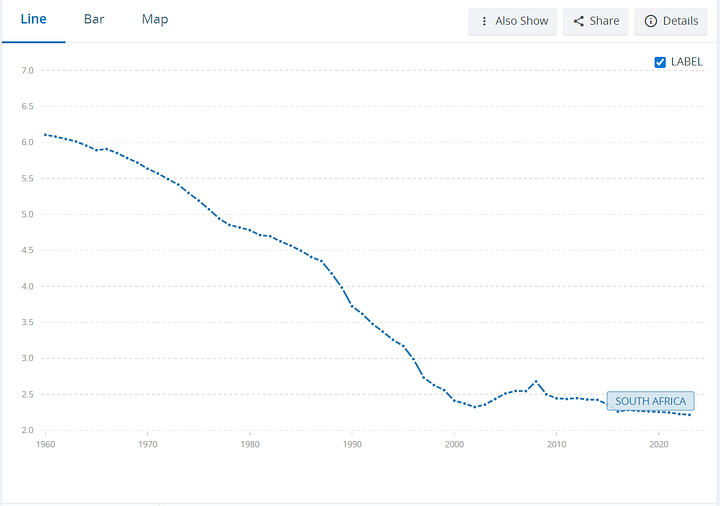

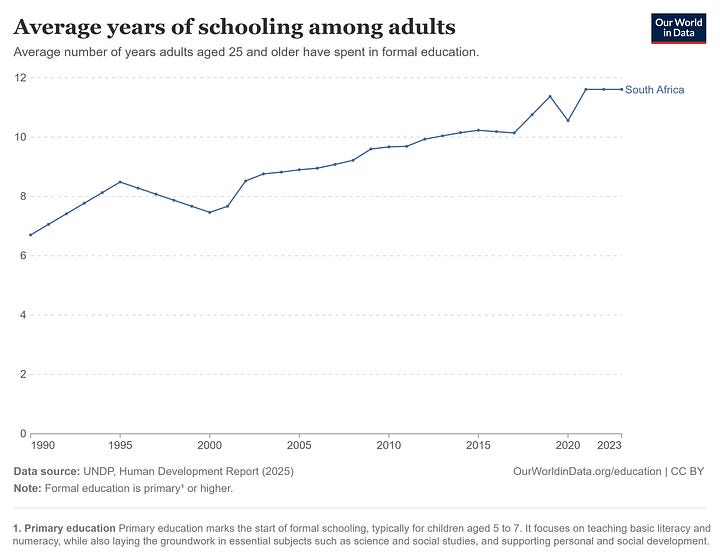

Last, but not least, let’s take a look at fertility rates and years of schooling in SA. The pictures below illustrate that SA is experiencing its own demographic transition. That’s also expected. Recall, as societies develop and become more urban, mortality rates decrease, the replacement effect is less of a priority, there’s an increase in returns and people start investing in the education of their own offspring, but education has opportunity costs. So the quantity-quality tradeoff. And the number of years of schooling has been on the rise, which is expected in a developing society, and great news. Recall, the services sector demands skills.

In all, SA isn’t a Malthusian economy. South Africa has a modern services sector, which could be even more modern, competitive and bigger (we have just to look at Rosebank and Sandton and the number of jobs being created there that require all sorts of skills). I don’t want this article to go for too long, but policy priorities should revolve around having better cities, with better and better located health and education facilities, better transportation systems integrating people with jobs, etc. Keeping people in the primary sector, including going down the mines, is certainly not the way forward for any developing country. Mines don’t need skilled people, mines demand brawn, not human capital. As Acemoglu highlighted, “it’s good jobs, stupid”!